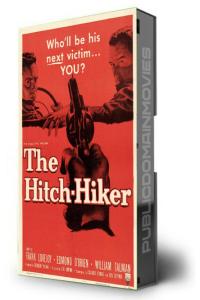

The Hitch-Hiker

The Hitch-Hiker (1953) – A Noir Masterclass in Paranoia and Tension

Ida Lupino’s The Hitch-Hiker (1953) is a lean, mean noir machine — a thriller that grips your throat and doesn’t let go until the credits roll. What makes it doubly fascinating is not just the raw tension of the narrative but the fact that this is the first American film noir directed by a woman. Lupino, already a star actress, stepped behind the camera with a precision and authority that still feels modern. Her direction is tight, never wasting a frame, and her ability to mine fear from silence and sweat is Hitchcockian. It’s a film built on atmosphere, claustrophobia, and the unsettling fact that it’s inspired by the true story of serial killer Billy Cook.

The plot is mercilessly simple: two men on a fishing trip pick up a stranded hitchhiker, who turns out to be a sadistic murderer on the run. From there, the film becomes a hostage story that stretches across the desolate highways of Baja California. William Talman, as the psychotic Emmett Myers, delivers a chilling performance — his lazy eye and deadpan menace make him one of noir’s great under-sung villains. Edmond O’Brien and Frank Lovejoy, as the unlucky duo, carry the film with quiet desperation. Their chemistry feels authentic, their fear palpable. The desert becomes a character in itself: endless, sun-bleached, and utterly indifferent to human suffering.

The Hitch-Hiker is in the public domain, which is fitting for a film that belongs to the people — a cinematic warning about trust, violence, and survival. Its status makes it easily accessible for free streaming, and it remains a must-watch for fans of classic film noir, true crime thrillers, or independent cinema history. Lupino’s work here deserves to be studied and celebrated — not just because she broke through a male-dominated industry, but because she delivered a taut, suspenseful film that still holds up seventy years later.